arc014: 'Scenius' and the Lens of Collective Contribution - SNAKE & FRIENDS, Hill Country Blues, EGO SUMMIT (Difficult Fun, 2018)

+++a seven-year old written ode to collectivity!___

I’d hoped to contribute something new by now, but am under the pump trying to finish a draft for a new novel coming very soon, so please let this 2018 article arrive in your inbox instead! This was written for short-lived website Difficult Fun, the archive of which is still alive in a slightly scrappy form, but worth browsing if you’re after some long reads. It started as a review about the 2018 SNAKE & FRIENDS LP, but soon blew out into something more expansive after I was tipped off to the notion of ‘scenius’ by Lena Molnar (ARMOUR, 100%, BLODLETTER) and some similar conversations I was having at the time with my then-housemate Toto Shorey (XILCH, PERSPEX, FULLY FEUDAL, GAYAB), brief workmate Nic Warnock (RIP SOCIETY, BED WETTIN BAD BOYS, MODEL CITIZEN), and some emails with Chloe Allison Escott (THE NATIVE CATS). I forgot I’d written it, and it’s a little sloppier than I’d like, but I’ve been recently thinking about this idea again so here we are. The need for city-wide communities to build sounds, ideas and ethics together lives on, and I was reminded of it after writing this recent review of Cher Tan’s Peripathetic: Notes on (un)belonging at the Sydney Review of Books. There, I try to make the case for coming together and opposing the big Other, but seems I’ve been retracing those steps for a long time. The SNAKE & FRIENDS LP still rules by the way, get a copy if you find it…

‘SCENIUS’ AND THE LENS OF COLLECTIVE CONTRIBUTION

Decades of social, cultural and political exposure have taught us to respect and worship the feats of individuals. We elect Prime Ministers and Presidents instead of parties. We acknowledge sole contributors for their hard work in collective projects. We consider ourselves in charge of our distinct destinies. We also find it hard to ask for help or to check in on others, and even when we use the collective ‘we’ — we’re usually talking about ourselves. This may seem like it’s always been the case, but individualism, self-reliance and resulting loneliness is mounting everywhere you look.

Writers like Jodi Dean (among many others) have been busy analysing the negative impacts of individualism and self-reliance as a parallel to free-market capitalism and neoliberalism, while journalist George Monbiot has coined our times the ‘Age of Loneliness.’ These parallels are shown in the decline of collective institutions like unions and parties (also in rising rates of mental illness), but while aspects of this may seem to be a generational symptom, in the arts, the idea of the individual and the genius is a historical mainstay.

In popular music, the crowd (the band) is often less prominent than the individual (the song-writer or producer), where geniuses are raised on pedestals that negate the existence of the communities that gave rise to their ‘genius’ status. While an individual can often foster a sense of community (and in the case of remarkable figures, can even draw attention to it), the notion of individual art ignores the world that helped build it. In 2008, Brian Eno coined the (admittedly sloppy) term of ‘scenius’ as a counterpoint to the individual genius, calling it, “the whole ecology of ideas that give rise to good new thoughts and good new work.” In witnessing underground music scenes through the years, this is a notion that resonates with me, even though Brian Eno is talking about it.

I look around at underground music communities and I see worlds that operate and feed into each other, building movements and common sounds that don’t exist anywhere else. I see ‘scenius’ every weekend, through ideas that flow into and out of each other that occasionally yield a record, or a memorable live show, or a song that sticks for reasons that are unexplainable. Architect Josep Antoni Coderch once wrote against the ‘genius’, identifying individuals and outcomes as “events” of collective thought, and there are certain records that come out of music scenes that feel the way to me too.

As the headline to this article suggests, this was meant to be a review of the SNAKE & FRIENDS LP released in early 2018 through Sydney label RIP Society. It’s a recording project by the busiest person in underground music, Al Montfort – but I apologise to Al and his fans as I focus on the ‘and Friends’ part here. In writing this, I grew to enjoy looking at Al and the Snake and Friends LP as events.

Underground music movements are an interesting lens to view the world through because they form and reform new contexts over short time frames. Bands are made to look, sound and feel as ‘one’ through extensions of a shared moment, as short-lived social phenomena (the whole feel of a city can change when a half dozen new bands form over a few months), or repetitive consistency (a city stagnates when the same bands play in support of each other every week). The underground is in constant flux, because in its very definition, it must exist in opposition to something. Its boundaries are loose, and its centre is hard to place: for it to be ‘underground’ it has to be ignored on some level. Scenes are built around collectives of people who are largely uninteresting to the bulk culture and, on very special occasions, a forgotten collection of sounds form and thrive without the attention of someone willing to co-opt it. Underground movements, then, can result in a kind of ‘forgotten scenius.’

This idea is pertinent beyond the more obvious worlds such as punk or DIY. The first example that comes to mind when I think of forgotten scenius is the sound of the Hill Country Blues, a distinct form of music developed in the north of Mississippi throughout the thirties and fourties, and went largely unrecorded until curious outsiders turned their eye to the region in the nineties, in no small part through the efforts of Fat Possum Records [Note: a detailed history of the Hill Country Blues via R.L. BURNSIDE appears in the BH podcast here.] The limitations of its players and the locations they played in built an underground scene with a lack of commercial appeal. This was primarily to do with their unusual structures: jamming on one chord, often changing only once (and then back again a while later), all made for holding a groove at parties and bars. It was cantankerous party music that existed for the benefit of nobody but the players and their community, and saw an explosion of interest when released by Fat Possum for the very qualities that had been ignored by the mid-century co-options of rock ‘n’ roll.

Central to the Hill Country Blues were people like JUNIOR KIMBROUGH (whose juke joint was a centre-point for the blues scene), R.L. BURNSIDE (whose early successes were fleeting, returning to Mississippi after a number of his family members were murdered in Chicago), CEDELL DAVIS (who contracted polio and lost use of his hands, forcing him to play guitar upside down with a butter knife as a slide, thus adding to the sound’s tinny repetition), JESSIE MAY HEMPHILL (drummer and solo musician often overlooked by the historians’ insistence on referring to them as the Hill Country Bluesmen), JOHNNY FARMER (who refused to record, and blamed the devil for striking him down with various illnesses after being coerced into putting his songs to tape) and many more. Their records have shared sounds and structures, to the point that their individual works really do feel like ‘events’ that grew out of their collective interests in their unique form of blues.

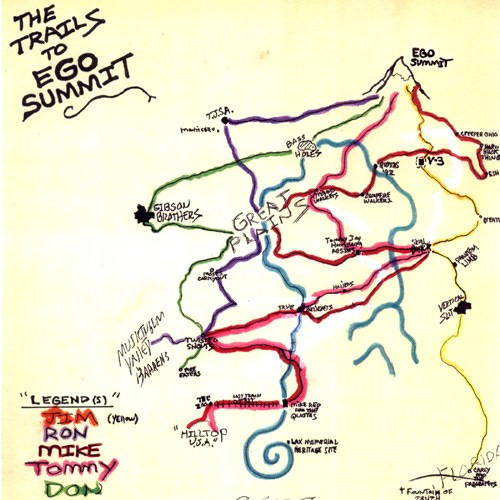

Moving closer to the kinds of communities and relationships that foreshadow SNAKE AND FRIENDS, are a collective of underground musicians who recorded around the ‘80s and ‘90s in Ohio. Unlike the Hill Country Blues players, they didn’t have a moniker to rally around, but their disparate recording projects cross over each other regularly enough to build a scene of interconnected sounds and ideas. Their version of scenius culminated with a collaborative event in 1997 with the EGO SUMMIT LP, The Room Isn’t Big Enough (as good a riff on the ‘supergroup’ tag as any).

The members of EGO SUMMIT (Ron House, Mike Rep, Tommy Jay, Don Howland, Michael Hummel and Jim Shephard; from bands including GREAT PLAINS, THOMAS JEFFERSON SLAVE APARTMENTS, THE QUOTAS, V-3 and more) threaded music from strange field recordings and experiments to ‘90s indie rock, all with a flippant sense of humour that clashed with moments of defeated depressions. They recorded to tape, distributed independently, and were stuck with only cult followings that last to this day.

The EGO SUMMIT record is one of my favourite examples of an event of scenius, taking aspects of country and folk and pairing it with honest acknowledgements of their place in the world. It is the perfect death knell to the 20th century, with cultural icons fading out (“We got Deadheads finally looking for jobs”) and their own scene dying as they do: “You’re not the one who’s getting old / You’re the one who’s dying out.” The depressions of the Hill Country Blues songs lead to the fatalism of EGO SUMMIT: they are interesting and ever-lasting when witnessed as events, and parallel the sociopolitical conditions of their time and place. If we take this notion and then turn towards worlds we’re more intimate with, we can view the formation of new scenius communities as events, even the Melbourne of 2018 that was responsible for SNAKE & FRIENDS.

The world connected to Al Montfort was drawn together in a mini-issue of Distort zine, handed out as a programme for the only ever SNAKE performance at the Sydney Opera House in 2014. Titled History of Hate, Power and People in Australia, 1986-2014, it included song lyrics prepared by Al that featured in recordings by SNAKE, TERRY, TOTAL CONTROL and RUSSELL STREET BOMBINGS. The zine gives a thematic preview to the 2018 SNAKE & FRIENDS record: context for songs like ‘Forever New’ and hints at what an instrumental track like ‘Mounting Evidence’ might be circling. The zine is a useful entry point, because it’s Al’s previous work and the surrounding texts that give Snake and Friends meaning as a collaborative event.

The first SNAKE tape was partly recorded on a four-track while travelling India, with the stilted practice of unusual instrumentation (Sarangi and Assamese buffalo horn) giving the project its unsettling cadence. But the loneliness of the first tape disappears on Snake and Friends, making way for contributions by a sprawling web of interconnected musicians. The record may primarily feature Al playing solo, but it also includes additions from Mikey Young and Zephyr Pavey (who with Al, make up RUSSELL STREET BOMBINGS), as well as Xanthe Waite and Amy Hill (who, along with Zephyr, comprise the band TERRY). Further still are the synth contributions of Nick Kuceli (who recently released the NKDX tape with Dan Stewart, who in turn is Al, Zephyr and Mikey’s TOTAL CONTROL band-mate). It’s hard not to witness this web of contributors as anything but scenius in action with all that in mind.

Enlighteningly, Al has always appeared as a contributor to a collective, and it’s no doubt intentional: even when “Snake” started to seem like a moniker, he necessarily added “and Friends” as a clarification. You can feel the strange folk of LOWER PLENTY on ‘Sight and Sound,’ the unsettled experimentation of RUSSELL STREET BOMBINGS on ‘Moe River,’ and parts of TERRY on ‘The Missus and the Masses.’ But there is a new (almost uncategorizable) sound on Snake and Friends. It’s more exploratory than many of the other works, and it’s hard to pinpoint a common sound beyond this intangible feeling of the eerie. The record may not find much of an audience, even with adoring fans of TOTAL CONTROL or DICK DIVER, simply because the reference points can’t be placed easily – or maybe because the record has little narrative to latch onto. [Note: Just realising that a lot of this review comprises the DICK DIVER / TOTAL CONTROL episode of the BH podcast here.]

Acknowledging records like Snake and Friends as an event rather than a celebration of one contributor’s song-writing chops feels like a positive way forward to me. As members of Monbiot’s ‘Age of Loneliness,’ concepts like scenius seem to me a vital and positive way of framing underground cultures. It gives us awareness that in the underground music communities, groups of people are in this together, and, by association, you and I are too — even as spectators.

The difficulty is that all this takes a bit of re-schooling. Most people will see music through in-built ascendency narratives that claim that an artist must improve along a linear trajectory to be important. From the bottom of the bill to the top, from a tape to a 7” and then an LP, from a smaller stage to a larger one. It’s ingrained in contemporary society that a group of musicians can’t just create, but need to grow and develop to be considered worthwhile. Healthier narratives would involve the redistribution and infiltration of ideas around a community and scene: it motivates people who have never contributed to join the chorus. I’d advocate more than anything for the breaking down of genius worship in favour of this concept of scenius: it has promise in encouraging contribution to the collective effort, and it’s something we should all aspire to if we’re to take ourselves seriously as members of an underground effort.

+++other updates___

__been a while since being interviewed for punk stuff, but Gimmie Gimmie Gimmie zine was kind enough to take an interest in the BH book and ask me onto a nice, long Q&A session that you can read here.

__i’m very close to selling out (ha ha ha)… of the second edition of the BARELY HUMAN book, so please leap on this quick if you like the colour green. i’ll print a third edition in due course, but gotta save some money up for the printing costs first.

__a quick note that i was going to add a paid option to this substack again because times are tough, however i’ve since scrapped that idea because: times are tough for everyone. this stuff will always be free, and i’ll try to only ever charge for things that have costs to cover.